Beyond 2.5D: A Review of Non-Planar Slicing Algorithms and Principal Stress Alignment in Robotic Continuous Fiber Printing

Vector-Field Based Toolpath Generation for Multi-Axis Composite Additive Manufacturing

FIGURE 1: Hero Image — Stress-Aligned Continuous Fiber Printing on Curved Surface

Principal Stress-Guided Spatial Fiber Printing

6-DOF robotic deposition of continuous fiber along σ₁ directions on non-planar toolpaths

Introduction

The vast majority of additive manufacturing systems—from desktop FDM printers to industrial fiber placement robots—operate under a fundamental constraint: they slice parts into flat, horizontal layers and deposit material in a plane-by-plane fashion. This "2.5D" paradigm works well for prismatic geometries but introduces significant limitations when manufacturing parts with curved surfaces, complex load paths, or where fiber orientation directly determines structural performance.

For continuous fiber reinforced composites, this limitation is particularly consequential. The mechanical properties of a carbon fiber composite are highly anisotropic: tensile strength and stiffness along the fiber axis can exceed transverse properties by an order of magnitude. When fibers are constrained to planar layers, they cannot follow the three-dimensional stress trajectories that actual loads create—resulting in suboptimal structural efficiency.

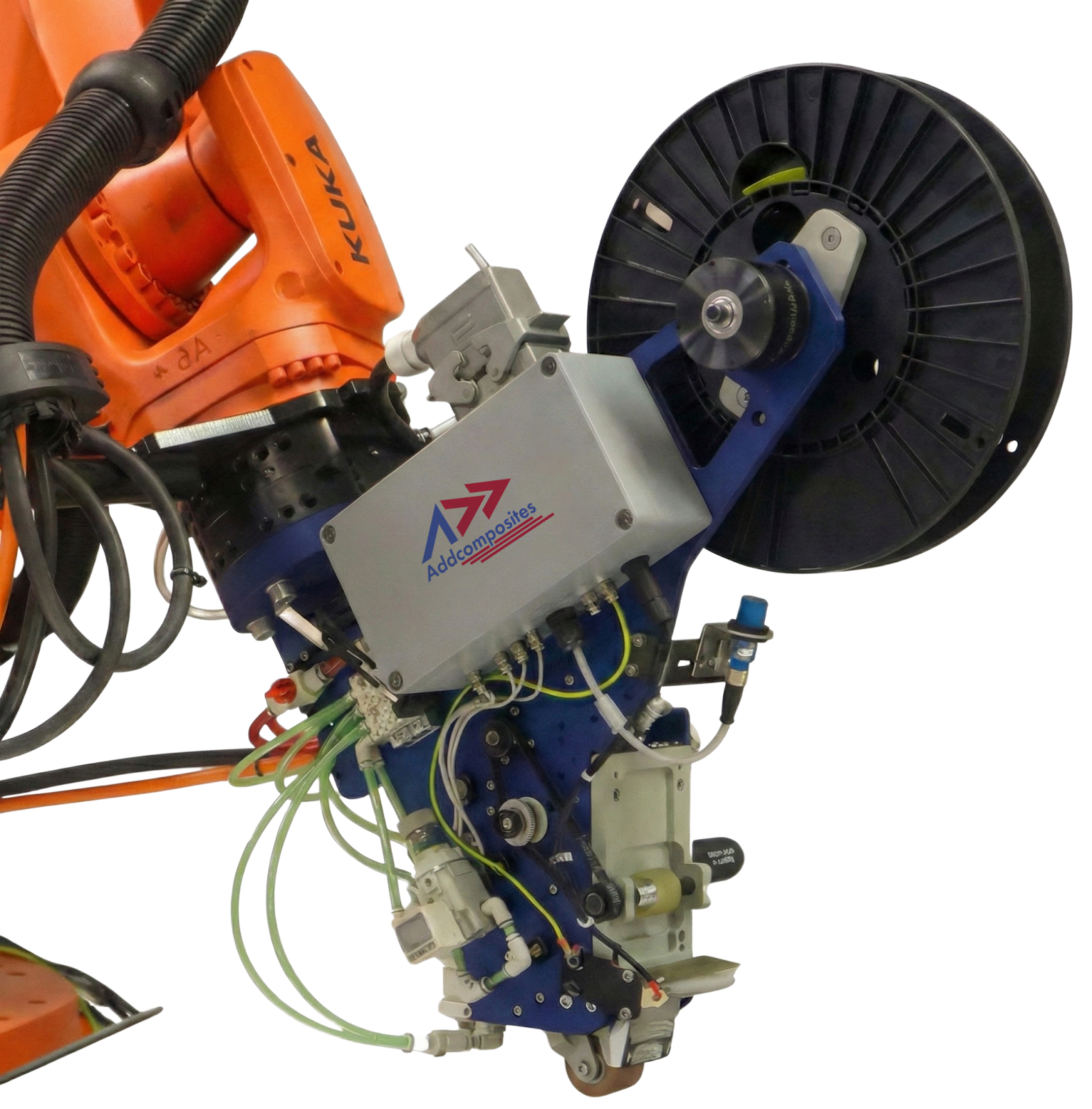

Multi-Axis Robotic Freedom

Compact AFP systems like the AFP-XS enable 6-DOF fiber placement on standard industrial robots. Multi-axis robotic systems possess the kinematic freedom to deposit material along arbitrary 3D paths. The question is no longer whether non-planar printing is mechanically possible, but rather: How do we generate toolpaths that exploit this freedom?

This review examines three interconnected algorithmic domains:

- Non-Planar Slicing — Algorithms that generate curved layers conforming to part geometry

- Stress-Field Aligned Toolpaths — Methods that derive fiber trajectories from FEA stress analysis

- Geodesic and Steered Path Planning — The mathematics of keeping fibers from buckling or lifting on curved surfaces

THE LITERATURE GAP

While planar slicing algorithms for FDM are mature and well-documented, the literature on vector-field based slicing—algorithms that generate toolpaths based on FEA stress analysis rather than simple geometric intersection—remains fragmented. Most published work focuses on either non-planar geometry OR stress alignment, but rarely integrates both into a unified framework suitable for robotic continuous fiber printing.

The 2.5D Limitation

What is 2.5D Printing?

In conventional additive manufacturing, parts are "sliced" by intersecting the 3D model with a series of horizontal planes at fixed Z-heights. The resulting 2D contours define the toolpath for each layer. The Z-axis moves only between layers—never during material deposition.

This approach has three consequences for continuous fiber composites:

FIGURE 2: The Staircase Effect in 2.5D Printing

Conformal Deposition

AFP-XS depositing continuous fiber conformally on a curved surface, eliminating the staircase effect inherent in 2.5D approaches.

Slicing Strategy Comparison: Planar vs Non-Planar

How layer geometry impacts surface quality, fiber continuity, and structural performance

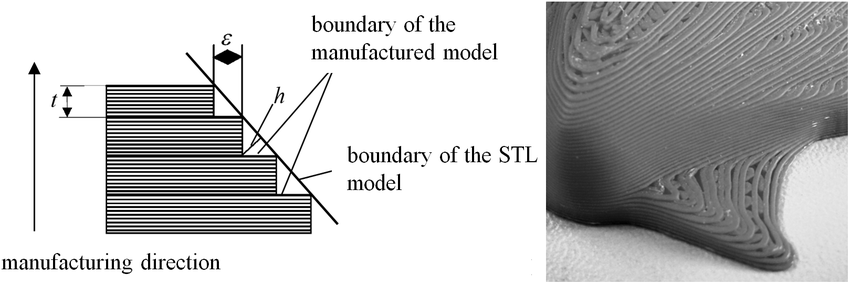

Consequence 1: The Staircase Effect

When a curved surface is approximated by planar layers, a "staircase" or "stair-stepping" artifact appears. For unfilled polymers, this is primarily an aesthetic and surface finish concern. For continuous fiber composites, it creates:

Fiber discontinuities at layer transitions

Stress concentrations at step edges

Reduced interlaminar strength due to geometric notches

Research by Ahlers et al. demonstrated that non-planar layers can reduce surface roughness by 63% compared to planar slicing

Consequence 2: Fiber Orientation Constraints

In 2.5D printing, fibers can only be oriented within the XY plane. They cannot:

- Follow out-of-plane curvature (e.g., dome surfaces)

- Align with 3D principal stress trajectories

- Wrap continuously around convex geometries

This fundamentally limits the structural efficiency achievable through fiber placement.

Consequence 3: Support Requirements

Complex overhanging geometries require support structures in 2.5D printing. Multi-axis non-planar approaches can orient the deposition head normal to the local surface, eliminating the need for supports on many geometries that would otherwise be unprintable.

Non-Planar Slicing Fundamentals

Taxonomy of Non-Planar Approaches

Non-planar slicing algorithms can be categorized by their primary objective:

| Approach | Primary Goal | Method | Key Papers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface-conforming | Eliminate staircase | Offset from top surface | Ahlers 2019, Chakraborty 2008 |

| Iso-surface | Functional optimization | Scalar field iso-surfaces | Fang 2024, Liu 2024 |

| Stress-aligned | Structural performance | FEA-driven vector fields | Fang 2024, Li 2022 |

| Geodesic | Manufacturing feasibility | Shortest paths on surfaces | Diehl 2013, Sun 2020 |

| Adaptive thickness | Material efficiency | Variable layer height | Allen 2020, Jin 2017 |

Non-Planar Slicing Strategies

Four approaches to generating curved-layer toolpaths for multi-axis deposition

The Collision Constraint

Any non-planar toolpath must be collision-free—the print head and robot arm must not intersect previously deposited material. This imposes geometric constraints that planar slicing trivially satisfies (always print from bottom to top) but non-planar slicing must explicitly solve.

QuickCurve (Etienne et al., 2024)

Addresses this through "slightly non-planar" surfaces that limit maximum deviation from horizontal, ensuring the nozzle always has clearance.

Neural Slicer (Liu et al., 2024)

Uses a learned neural network to optimize slicing surfaces while satisfying collision constraints through an energy-based formulation.

Iso-Surface Slicing Algorithms

The Isothermal Analogy

One elegant approach to generating curved slicing surfaces comes from thermal simulation. Proposed by Xu et al. (2022), the method works as follows:

- Place the model virtually on a heated freeform substrate

- Simulate heat conduction through the model

- Extract isothermal surfaces (surfaces of constant temperature)

- Use these isotherms as slicing layers

Isothermal Surface Slicing

Using steady-state thermal fields to generate naturally conformal non-planar layers

The temperature field T(x,y,z) satisfies Laplace's equation:

By tailoring boundary conditions (base temperature, ambient temperature, surface convection) and assigning different thermal conductivities to regions of the model, the resulting isotherms can be shaped to achieve:

- Conformal layers following the substrate

- Variable layer thickness based on local geometry

- Smooth transitions between regions

Reported improvements:

Scalar Field Optimization

More generally, non-planar layers can be generated by computing an optimal scalar field φ(x,y,z) and extracting its level sets (iso-surfaces) as slicing layers.

The design problem becomes: What scalar field produces iso-surfaces that satisfy our objectives?

Objectives may include:

- Conforming to top surfaces (minimize staircase)

- Aligning with stress directions in critical regions

- Maintaining printable layer thickness

- Avoiding collisions

Liu et al. (2024) formulate this as a differentiable optimization:

Where:

- ℒsurface penalizes deviation from target surface

- ℒcollision penalizes print head collisions

- ℒthickness maintains uniform layer thickness

Principal Stress-Aligned Toolpaths

The Structural Optimization Motivation

For continuous fiber composites, fiber orientation is not merely a manufacturing parameter—it determines structural performance. Aligning fibers with principal stress directions maximizes the utilization of the fiber's tensile properties.

Principal Stress Field (σ₁) — Plate with Central Hole

How tensile load redistributes around a discontinuity, and why fiber alignment matters

Fibers cut at hole boundary. No load transfer around the discontinuity — stress concentrations remain at the theoretical maximum.

Fibers wrap continuously around the hole following σ₁ streamlines. Load transfers smoothly — effectively eliminates the stress concentration.

FEA-Driven Toolpath Generation

The general workflow for stress-aligned toolpath generation:

FEA-to-Toolpath Pipeline

From CAD model to stress-aligned deposition paths in five computational steps

The Vector Field Problem

The stress tensor at each point yields principal directions through eigenvalue decomposition:

Where v₁ corresponds to the maximum principal stress direction (the optimal fiber alignment for tension-dominated loading).

Challenge: The vector field formed by v₁ directions is typically:

Not smooth — Discontinuities at material boundaries

Not divergence-free — Streamlines may converge/diverge

Singular — Undefined at isotropic stress states where σ₁ = σ₂

Field-Based Toolpath Methods

Li et al. (2022) proposed a field-based toolpath generation approach that addresses these challenges:

- Harmonic field smoothing — Project the stress directions onto a smooth vector field

- Stream surface generation — Create surfaces whose tangent aligns with the smoothed field

- Iso-curve extraction — Extract toolpaths as curves on the stream surfaces

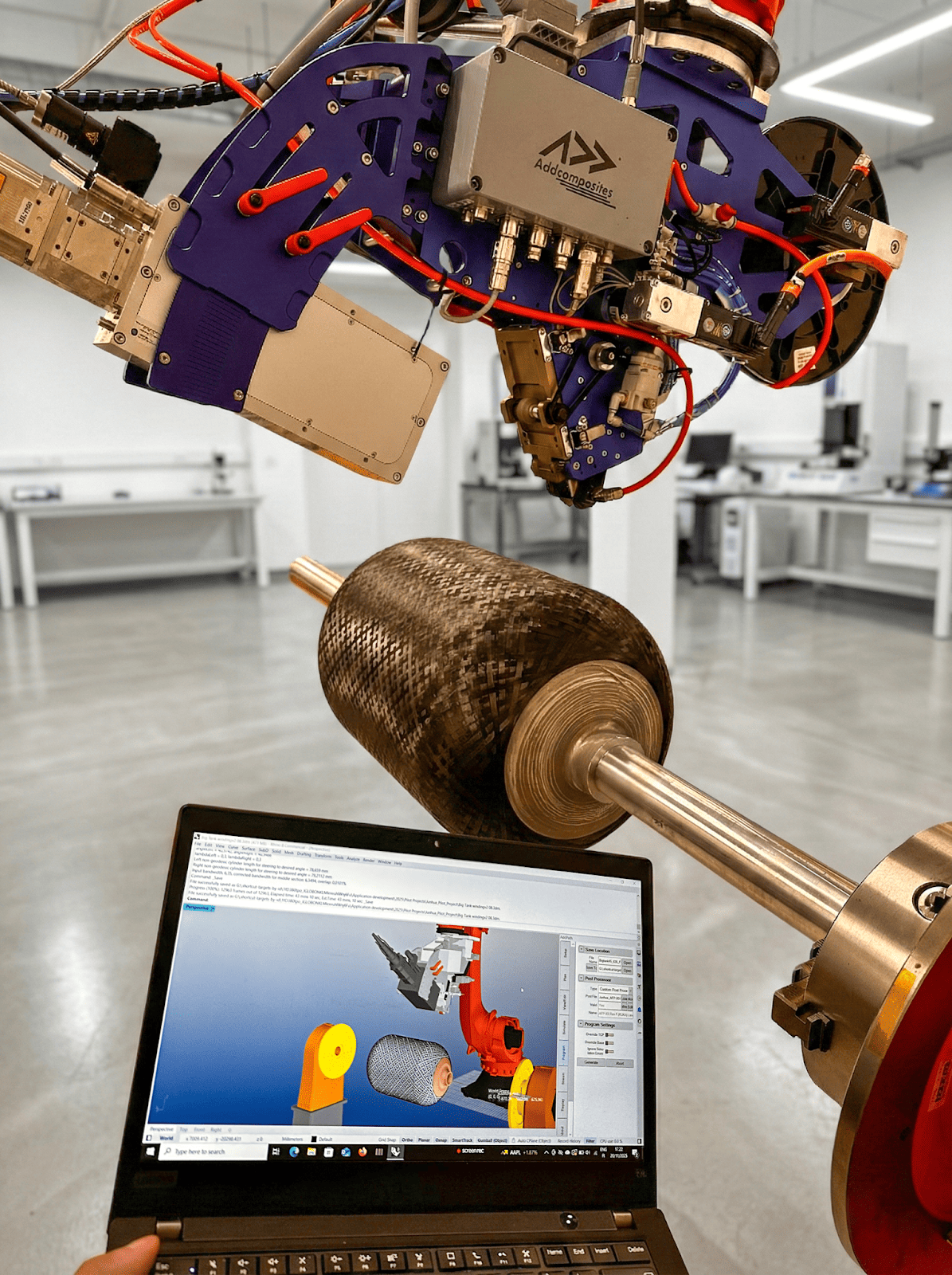

Digital Twin to Physical Part

From digital twin to physical part: AddPath simulation and corresponding AFP-XS deposition.

From Stress Field to Toolpaths

Four-stage pipeline: stress tensor → smoothed vector field → streamlines → printable fiber paths

Raw Stress Field

Smoothed Vector Field

Streamline Integration

Final Toolpaths

Source: Li et al. (2022), "Field-Based Toolpath Generation for 3D Printing Continuous Fibre Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites," Additive Manufacturing, 49.

Principal Stress Lines (PSL)

An alternative approach extracts Principal Stress Lines directly from the stress field—curves that are everywhere tangent to a principal stress direction.

Fang et al. (2024) demonstrated that PSL-based toolpaths achieve significantly higher fiber coverage in regions of stress concentration compared to raster patterns:

| Method | Fiber Coverage | Load Capacity vs. XY-Planar |

|---|---|---|

| XY-planar raster | ~65% | 1.0× (baseline) |

| Principal stress lines | ~90% | 6.35× |

| Stress-aligned iso-surfaces | ~85% | 4.5× (5-DOF system) |

The key finding: stress-aligned toolpaths in critical regions dramatically improve structural performance, with reported load capacity improvements of 4-6× compared to conventional planar approaches.

Geodesic vs. Steered Fiber Paths

The Path Geometry Problem

When depositing continuous fiber on a curved surface, the fiber path must satisfy geometric constraints to avoid defects. Two fundamental path types exist:

Geodesic Paths

The shortest path between two points on a surface (zero geodesic curvature)

Steered Paths

Paths that deviate from geodesics to achieve desired fiber orientation

Geodesic vs. Steered Paths on Curved Surfaces

Comparing zero geodesic curvature (κg = 0) and variable-angle steering (κg ≠ 0) strategies for AFP

| Property | Geodesic (κg = 0) | Steered (κg ≠ 0) |

|---|---|---|

| Fiber Tension | Uniform along path Stable

|

Variable — higher at inner radius Monitor

|

| Slippage Risk | Low — natural adherence Low

|

High — lateral force on tow High

|

| Wrinkling Risk | None — zero in-plane curvature None

|

Possible — inner-edge compression Risk

|

| Orientation Control | Limited — geometry-dictated Fixed

|

Full — any angle achievable Flexible

|

| Path Coverage | Natural spacing — may diverge Gaps

|

Controllable — gaps/overlaps tunable Tunable

|

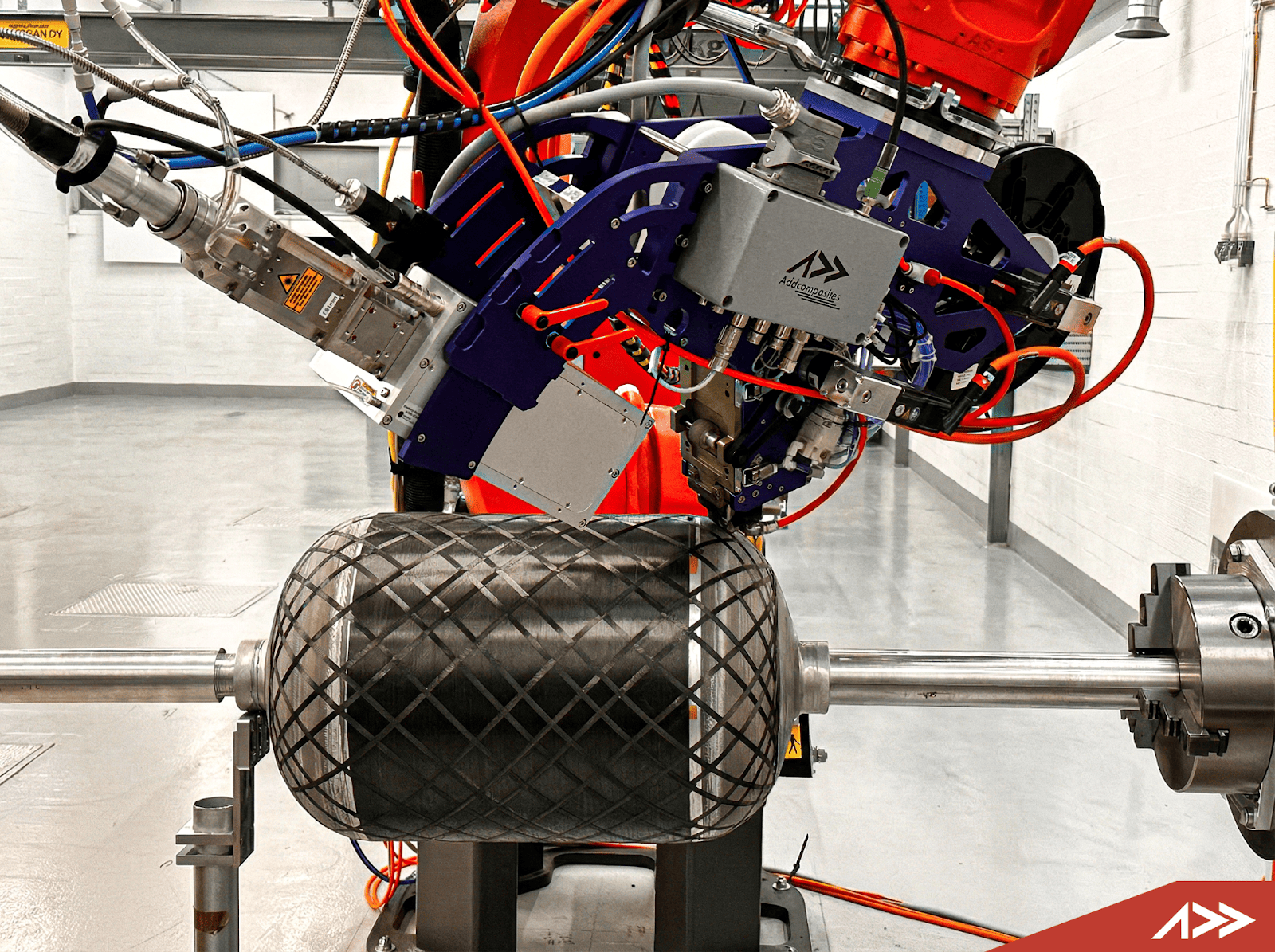

Geodesic Fiber Placement

AFP-XS performing geodesic fiber placement on a cylindrical mandrel, demonstrating the system's multi-axis path following capability.

Mathematical Framework

On a curved surface, a path γ(s) parameterized by arc length has two curvature components:

A geodesic is a path with κg = 0. For fiber placement:

The fiber experiences lateral forces proportional to geodesic curvature. When κg exceeds a threshold, the fiber will buckle/wrinkle on the inside of the curve (compression) or lift/slip on the outside of the curve (tension).

Steering Radius Limits

The minimum steering radius Rmin defines the tightest curve a fiber tow can follow without defects:

Typical values for carbon fiber prepreg:

| Tow Width | Material | Min Steering Radius | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6.35 mm (1/4") | CF/Epoxy | 500-700 mm | Industry standard |

| 3.175 mm (1/8") | CF/PEEK | 300-400 mm | Lukaszewicz 2012 |

| 6.35 mm (1/4") | CF/PEKK | 400-600 mm | Experimental |

The minimum steering radius depends on tow width (wider = larger radius required), matrix tack (lower tack = more slippage), substrate curvature (affects normal forces), compaction pressure (higher = better adhesion), and deposition temperature (affects matrix flow).

FIGURE 8: Steering Defects in Variable Angle Tow Placement

Defects from Excessive Steering

Three primary manufacturing defects in variable-angle AFP when geodesic curvature exceeds process limits

(from gaps)

(from overlaps)

(both gaps & overlaps)

Variable Angle Tow (VAT) Laminates

Variable Angle Tow composites intentionally use steered fiber paths to tailor stiffness distribution. The fiber angle varies continuously across the laminate, typically described by:

Where θ₀ is the angle at the center and θ₁ is the angle at the edge, over half-width L.

Benefits of VAT:

- Improved buckling resistance (up to 80% higher critical load)

- Tailored load paths around cutouts

- Reduced stress concentrations

- Optimized stiffness-to-weight ratio

Manufacturing challenges:

- Gaps and overlaps at path boundaries

- Thickness variation

- Process parameter optimization

- Requires steering within Rmin limits

Continuous Tow Shearing (CTS)

An alternative to traditional AFP steering, Continuous Tow Shearing (CTS) uses the ability to shear dry fiber tows rather than bend them:

Continuous Tow Shearing (CTS) vs. Conventional AFP Steering

Fiber steering mechanism comparison for variable angle tow composites

Conventional AFP

~500 mm

Minimum Steering Radius

For 6.35 mm (¼") tow width

Continuous Tow Shearing

~50–100 mm

Minimum Steering Radius

Depending on shear angle limit

Source: Beakou et al. (2014), "Manufacturing characteristics of the continuous tow shearing method," Composites Part A, 66.

CTS Advantages

- Significantly tighter steering radii (5-10× improvement)

- Reduced process-induced defects

- Better fiber alignment with designed orientation

CTS Limitations

- Currently limited to dry fiber (subsequent infusion required)

- Shear strain limits exist (typically < 30°)

- Equipment more complex than standard AFP

Manufacturing Constraints

Multi-Axis Robot Kinematics

6-DOF industrial robots provide the kinematic freedom for non-planar printing, but introduce constraints:

Robot Workspace Constraints

FIGURE 10: Robot Workspace and Singularity Constraints. The reachable workspace, joint limits, singularities, and collision boundaries all constrain the toolpath planning envelope.

6-DOF Robot Considerations for Non-Planar Printing

Workspace, kinematic constraints & toolpath requirements for robotic AFP/LFAM

Reachable Workspace Envelope

Kinematic Constraints

Joint Limits

Each axis has ±θmax rotational bounds

→ Limits reachable orientations at workspace edges

Singularities

Wrist singularity at extended reach positions

→ Infinite joint velocities near singular configs

Collision Avoidance

Self-collision & environment collision checks

→ Real-time swept volume monitoring required

Velocity Limits

Max joint speeds constrain TCP velocity

→ Non-uniform deposition if TCP speed varies

Acceleration Limits

Dynamic limits for smooth motion profiles

→ Critical for fiber tension & compaction control

Toolpath Requirements for Non-Planar Deposition

Continuous Orientation

Smooth orientation changes along path — avoid wrist flip discontinuities

Reachable Envelope

Entire part must fit within the robot's feasible workspace

Constant TCP Velocity

Uniform speed at tool center point for consistent material deposition

Smooth Acceleration

Jerk-limited profiles for fiber tension and compaction force control

Process Parameter Interdependencies

Non-planar continuous fiber printing involves coupled parameters:

| Parameter | Planar Printing | Non-Planar Complexity |

|---|---|---|

| Layer height | Constant | Varies with surface normal |

| Deposition rate | Constant | Varies with curvature |

| Compaction force | Normal to bed | Normal to local surface |

| Temperature | Uniform | Varies with head orientation |

| Robot speed | 2-DOF (XY) | 6-DOF, joint-limited |

Collision Detection

Non-planar toolpaths require explicit collision checking:

Nozzle-to-part collision — The print head must not hit already-printed material

Robot-to-part collision — Robot links must clear the part

Robot-to-environment collision — Fixtures, enclosure, etc.

Modern slicers address this through configuration space analysis (C-space obstacles), signed distance fields for fast collision queries, and incremental collision checking along toolpath.

Performance Improvements

Structural Performance Gains

Published studies report dramatic improvements from stress-aligned and non-planar toolpaths:

Mechanical Performance: Stress-Aligned vs. Conventional

Load capacity and stress concentration improvements through optimized fiber orientation

Load Capacity Comparison

Normalized to XY-Planar baseline = 1.0×

Stress Reduction at Notch / Hole

Stress concentration factor comparison

3.0×

Straight Fiber SCF

0.94×

Stress-Adapted SCF

3.2×

Stress Reduction

Sources: Fang et al. (2024), arXiv:2410.16851; Sugiyama et al. (2022), Progress in Additive Manufacturing.

Key Performance Data

| Study | Method | Test Case | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fang 2024 | PSL + iso-surfaces | Tensile specimens | 6.35× load capacity |

| Fang 2024 | 5-DOF stress-aligned | Hemispherical caps | 4.5× burst pressure |

| Sugiyama 2022 | Stress-adapted | Plate with hole | 3.2× stress reduction |

| Matsuzaki 2016 | Curved layer FDM | Beam bending | 25% stiffness increase |

| Li 2022 | Field-based | Bracket | 90% fiber coverage |

Surface Quality Improvements

Non-planar slicing also improves surface finish:

| Method | Surface Roughness (Ra) | Improvement vs. Planar |

|---|---|---|

| 2.5D planar (0.2mm layer) | 10-15 μm | Baseline |

| Surface-conforming | 3-5 μm | 63% reduction |

| Adaptive thickness | 5-8 μm | 40% reduction |

| Isothermal surfaces | 4-6 μm | 55% reduction |

Computational Methods

Topology Optimization Integration

The most advanced approaches integrate toolpath generation with topology optimization:

Integrated Topology and Toolpath Optimization

Simultaneous material layout & fiber path optimization for layer-free multi-axis AM

Design Inputs

Topology Optimization

ρ(x, y, z) — density field

Toolpath Optimization

φ(x, y, z) — scalar field for iso-surface extraction

Outputs

Optimized Geometry

Topology-optimized shape with minimum compliance

ρ(x,y,z) → solid/void boundaries

Optimized Fiber Paths

Stress-aligned orientations on iso-surfaces

φ(x,y,z) → principal stress alignment

Printable Toolpath

Collision-free multi-axis deposition path

Robot-ready G-code / waypoints

Source: Zhou et al. (2025), "Simultaneous Topology and Toolpath Optimization for Layer-Free Multi-Axis Additive Manufacturing," Additive Manufacturing.

Algorithm Complexity

| Algorithm Component | Complexity | Typical Runtime |

|---|---|---|

| FEA solve | O(n³) | Seconds to minutes |

| Eigenvector decomposition | O(n) per element | Fast |

| Vector field smoothing | O(n log n) | Seconds |

| Streamline integration | O(m × n) | Seconds |

| Collision detection | O(p × log n) | Per-point check |

| Toolpath optimization | Iterative | Minutes to hours |

Where n = mesh elements, m = number of streamlines, p = toolpath points.

AddPath Platform

AddPath: integrated path planning, simulation, and robot code generation for automated fiber placement — from design to manufacturing in a single environment.

Software Tools

| Tool | Type | Non-Planar Support | Stress Alignment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cura | Open-source | Plugin (limited) | No |

| PrusaSlicer | Open-source | No | No |

| S4-Slicer | Research | Yes | No |

| FullControl | Python library | Yes | Research |

| ADDCOMPOSITES | Commercial | Yes | Yes |

| Ansys ACP | Commercial | Yes | FEA integration |

Industrial Applications

FIGURE 13: Aerospace Application Examples

Aerospace Applications — Non-Planar Continuous Fiber

Structural performance gains through stress-aligned, multi-axis fiber deposition

Pressure Vessel / Dome

Helical fiber winding paths follow geodesic trajectories on dome surfaces, aligning fibers with principal hoop and meridional stresses for maximum burst resistance.

4.5×

Burst Pressure vs. Planar

Load-Carrying Panel with Cutout

Continuous fibers are steered around structural cutouts, following principal stress trajectories to minimize stress concentration at hole boundaries.

3× Reduced

Stress Concentration

Conformal Tooling

Non-planar deposition conforms fiber layers directly to curved mold surfaces, eliminating inter-layer stepping artifacts and achieving near-net-shape surface accuracy.

<0.1 mm

Surface Accuracy

Current Industrial Implementations

| Company | Application | Technology | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9T Labs | Structural brackets | Stress-optimized, planar | Production |

| Arevo | Bike frames | Multi-axis, non-planar | Production |

| Continuous Composites | Large structures | 7-axis robot | Development |

| CEAD | Large-scale AM | Gantry, non-planar capable | Production |

| AddComposites | Research systems | AFP robot integration | Commercial |

Future Directions

Near-Term Developments (2025-2028)

- Unified slicing frameworks integrating non-planar geometry, stress alignment, and collision avoidance

- Real-time adaptive toolpaths responding to in-situ process monitoring

- Multi-material non-planar printing with strategic material placement

- Standardization of non-planar toolpath formats (beyond G-code)

Medium-Term Research (2028-2032)

- AI-driven toolpath optimization — Neural networks trained on FEA data predicting optimal paths

- Closed-loop stress-adaptive printing — Real-time FEA updates during printing

- Hybrid manufacturing — Integration with CNC machining for final surfaces

- Certification pathways — Qualification methods for non-planar printed primary structure

Open Research Questions

- How to handle multi-load case optimization when stress fields differ?

- What are the fatigue implications of stress-aligned vs. traditional laminates?

- Can machine learning predict steering defects before they occur?

- How to certify parts with spatially varying fiber orientation?

Conclusions

Summary of Key Findings

The 2.5D constraint is no longer necessary. Multi-axis robots provide kinematic freedom for true 3D toolpaths, and algorithms exist to exploit this freedom.

Non-planar slicing reduces surface roughness by 50-65% and eliminates the staircase effect on curved geometries.

Stress-aligned toolpaths improve structural performance by 3-6× compared to conventional raster patterns, particularly in regions of stress concentration.

Geodesic paths are manufacturing-safe but orientation-limited. Steered paths offer orientation control but require careful attention to steering radius limits.

Integrated topology and toolpath optimization represents the frontier, simultaneously optimizing what to print and how to print it.

Manufacturing constraints remain critical. Minimum steering radius, collision avoidance, and robot kinematics constrain the theoretical optimum.

Practical Guidance

For engineers considering stress-aligned non-planar printing:

| Application | Recommended Approach | Key Constraints |

|---|---|---|

| Pressure vessels | Geodesic + slight steering | Fiber continuity |

| Panels with holes | PSL-aligned | Steering radius at concentration |

| Complex 3D surfaces | Iso-surface + field-based | Collision, robot reach |

| Production parts | Start with planar VAT | Manufacturing maturity |

| R&D/prototypes | Full non-planar, stress-aligned | Compute time |

The Bigger Picture

Non-planar slicing and stress-aligned toolpaths represent a fundamental shift in how we think about additive manufacturing. Rather than asking "how do we manufacture this shape?" we can now ask "what shape and fiber arrangement optimally carries these loads?"

For continuous fiber composites, this is transformative. The anisotropy that makes composites challenging to design with becomes an opportunity when fiber placement can be optimized in three dimensions.

The technology readiness is advancing rapidly. Within the next 5 years, stress-aligned non-planar printing will likely transition from research demonstrations to production applications, first in aerospace (where performance justifies cost) and eventually in automotive and industrial applications.

The limiting factor is no longer the robot or the material—it's the algorithms and software that bridge the gap between structural design and manufacturing execution.

References

[1] Ahlers, D., Wasserfall, F., Hendrich, N., Zhang, J. (2019). 3D Printing of Nonplanar Layers for Smooth Surface Generation. IEEE CASE 2019. DOI

[2] Fang, G., et al. (2024). Toolpath Generation for High Density Spatial Fiber Printing Guided by Principal Stresses. arXiv:2410.16851

[3] Fang, G., et al. (2024). Exceptional mechanical performance by spatial printing with continuous fiber: Curved slicing, toolpath generation and physical verification. Additive Manufacturing, 82, 104048.

[4] Liu, H., et al. (2024). Neural Slicer for Multi-Axis 3D Printing. ACM Transactions on Graphics, 43(4). DOI

[5] Li, B., et al. (2022). Field-Based Toolpath Generation for 3D Printing Continuous Fibre Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites. Additive Manufacturing, 49, 102467. DOI

[6] Xu, J., et al. (2022). Additive manufacturing of non-planar layers using isothermal surface slicing. Journal of Manufacturing Processes, 84. DOI

[7] Etienne, J., et al. (2024). QuickCurve: Revisiting slightly non-planar 3D printing. arXiv:2406.03966

[8] Sugiyama, K., et al. (2022). Stress-adapted fiber orientation along the principal stress directions for continuous fiber-reinforced material extrusion. Progress in Additive Manufacturing. DOI

[9] Shirinzadeh, B., et al. (2019). Automated Fiber Placement Path Planning: A state-of-the-art review. Computer-Aided Design and Applications, 16(2), 172-203.

[10] Beakou, A., et al. (2014). Manufacturing characteristics of the continuous tow shearing method for manufacturing of variable angle tow composites. Composites Part A, 66. DOI

[11] Heinecke, F., Willberg, C. (2019). Manufacturing-Induced Imperfections in Composite Parts Manufactured via Automated Fiber Placement. Journal of Composites Science, 3(2). DOI

[12] Allen, R., Trask, R. (2020). Additive manufacturing of non-planar layers with variable layer height. Additive Manufacturing, 36, 101556.

[13] Jin, Y., et al. (2017). Variable-depth curved layer fused deposition modeling of thin-shells. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing, 48, 25-35.

[14] Lukaszewicz, D.H.J.A., et al. (2012). The engineering aspects of automated prepreg layup: History, present and future. Composites Part B, 43(3), 997-1009.

[15] Zhou, Y., et al. (2025). Simultaneous Topology and Toolpath Optimization for Layer-Free Multi-Axis Additive Manufacturing of 3D Composite Structures. Additive Manufacturing. DOI

[16] Fernandez, F., et al. (2025). Non-planar 3D printing: Enhancing design potentials by advanced slicing algorithms and path planning. Procedia CIRP.

[17] Wang, Z., et al. (2024). A fully automatic non-planar slicing algorithm for the additive manufacturing of complex geometries. Additive Manufacturing, 71, 103583. DOI

[18] Diehl, T., et al. (2013). Function-aware slicing using principal stress line for toolpath planning in additive manufacturing. Journal of Manufacturing Science and Engineering.

[19] Sun, Z., et al. (2020). An efficient pre-analysis and optimization generation method for reference curves of automated fiber placement path planning. Journal of Composite Materials. DOI

[20] CompositesWorld (2024). Automated fiber placement: The evolution from industrial to accessible.

Learn More

Have questions about implementing non-planar slicing and stress-aligned toolpaths for your composite manufacturing?

Contact Us for a Consultation